If not for the giant scars on the margins of its valley, Silver City would be on my short list of retirement options.

An elevation of 6,000 feet might be the ideal middle ground in the Desert Southwest, and easy access to much higher ground is a major asset. It is several hours from any significant urban center, and, of those, Phoenix is the only real metropolis.

Probably the strongest attraction is its vibrant arts community. It has dozens of studios, proudly marked by plaques on the vintage brick buildings, and most of the residences close to the downtown area, have murals, mosaics, antiques, sculptures decorating the tiny properties.

Many of the old storefronts are now quaint specialty restaurants. A short but elegant river walk along the creek running parallel a block from Bullard Street, the main downtown strip, shows the value that the residents place on peace of mind. The cool depths of the ravine, with its towering sycamores and cottonwoods, surely offers a necessary sanctuary during the hottest months.

A whitewashed cluster of century-old buildings presides over the historic quarter, the campus of the University of Western New Mexico – seemingly too large for the rural population but perhaps more in proportion with the size and status of the mines. Looming over the whole scene is Boston Hill Open Space, an undeveloped mountain dome with a network of trails that’s easily accessible to any resident.

Away from the crowd

U.S. 180 between Silver City and Alpine, across the state line in Arizona, is a journey through undeveloped America, and through the entire western fringe of the Gila National Forest. For many miles the road traverses unspoiled panoramas of chaparral, finally dropping into the valley of the Gila as it drains south out of the highlands.

Around the community of Cliff, where the river is joined by several tributaries – a couple of them referred to as “ditches” – the highway jogs northwest along Duck Creek, with the Mogollon Mountains looming to the right. Here, the surface atmosphere was clear and fresh, though a long brown smudge showed where smoke from the Tadpole fire rose to the level of the prevailing winds and jetted north.

At the Glenwood Trading Post, we stopped for supplies and yet another glimpse of the gaping cultural divide – with some wearing their face coverings, others oblivious. Change is never a welcome guest at a place like this. Only a couple of days later, the executive order would come down from Santa Fe requiring visitors from many states, including Arizona, to quarantine for two weeks.

A dip on a hot day

Glenwood also is the turnoff to the Catwalk Recreation Area, a popular day destination in the Gila National Forest, nestled into Whitewater Creek. That day was very bright and hot, especially considering the elevation – all the more reason, perhaps, that the parking lot was packed even on a Monday afternoon during a pandemic. We did have to wonder if these might mostly be locals.

Most of the visitors were there to stroll along at least a portion of the namesake walkways, but lots of groups – none, of course, equipped with face coverings – unloaded from their vans in wading attire and loaded picnic baskets.

We began our ascent along the original dirt path above the west side of the creek, but at the half-mile point converged with the foot traffic from the newer stretch of catwalk that hangs over the opposite bank. For a ways, the canyon is a narrow slot, the creek gurgling below the walkway grating in a series of inviting pools.

A central platform features historical plaques about the heyday of the canyon, where for a brief time ore was carried out from upstream using a system of cables and catwalks. How commendable that the place could be transferred to the public domain before it was entirely degraded.

The last half mile of the trail is more strenuous, and, where the stream finally disappears among imposing boulders, winding up out of sight toward the canyon rim, we took a precarious dip in a couple of hard-to-reach pools. We weren’t entirely dressed for mixed company, so to speak, when a nice guy from Tucson had to give us a hand back up the rock face.

The road that time forgot

About a fifth of the Gila National Forest is designated as wilderness, the western half of which is taken up by the Mogollon Mountains, the highest points in the vicinity. A state road that scarcely deserves that designation jumps from Hwy 180 up to the soaring ridges and then follows the northern boundary of the Wilderness.

The single-lane road is at least paved up to Mogollon, a historic mining town clinging to the two sides of the canyon draining Silver Creek. During normal times, art galleries, antique shops and a novelty museum or two would have been open. As it was, everyone summering at one of these restored houses was hunkered down out of sight, their Land Rover or Volvo parked safely beyond the “Posted” sign hanging across their private bridge.

Beyond the town, the route turns to dirt, and, though it is designated on the map as an “all-weather” road, it has clearly been overlooked by the maintenance crews for years. It might not be the roughest road I’ve ever been on, but definitely the worst I’ve ever tried to navigate with a travel trailer.

View from above

Thirty-odd miles took around four hours. Without a doubt, the winding track, which folds back and forth along a series of ridges, affords the best views in the entire forest. Unfortunately, most of that forest was consumed in a holocaust eight years ago, the largest in New Mexico history, leaving a patchwork of burned areas ranging from a few healthy thickets of pine saplings to vast stands of blackened stalks jutting from barren, crumbled rock.

I drove on and on at all of 10 miles per hour, afraid I’d be changing a tire as darkness fell. We did make it to Willow Creek with some light left, but the campground there was not open as we were promised at the Park Headquarters in Silver City. We drove with some annoyance past the locked barriers and up the creek road, past the Fish and Wildlife research station and the closed Ranger station. We didn’t spot any place appropriate for boondocking, but we did see signs of rich wildlife.

Finally, we came to private property, designated unambiguously by a metal gate, in front of which had generously been created a turnaround big enough for our rig. Back among the trees stood a couple of multistory houses along with their requisite outbuildings and various vehicles. Close enough to Paradise. I had been wondering where the One Percent were holing up for their bird’s-eye view of the pandemic.

Noble company

On the Forest Service map, the 10 miles leading to Snow Lake looked a lot smoother than what we had just done. Being skeptical, though, and having breathed enough dust for one day, we decided to set up at the picnic table sitting by itself in an open area at the foot of the valley, where the stream jogged away for its rendezvous with Gilita Creek.

Just as we were arriving, a couple of tough-looking women – tattoos, tank tops, wallet chains – were just locking up the vintage travel trailer that was backed up to the base of the slope. It turned out we wouldn’t have camping company because, in the two days we were there, they never returned. We had a lot of fun, though, imagining what role this little refuge played in their lives.

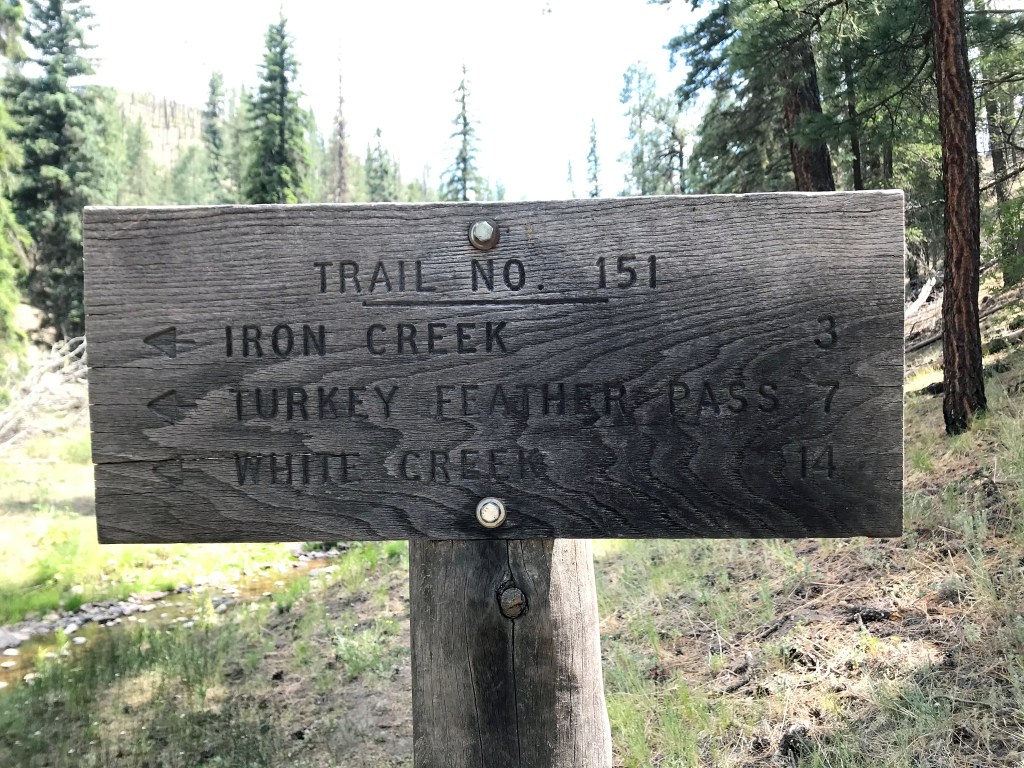

We woke up early, as one does in the outdoors, ready to revive our rusty skills at reading a topo map. The only clear opportunity for a hike from here was across the creek and up one of the nearby drainages to a ridge hidden from sight by a healthy stand of pine – destination, a feature labeled as Iron Creek Lake.

Predictably, we found the “lake” to be a stagnant reservoir at the top of a gentle glen, held back by a berm that doubles as the trail. As soon as the depleted puddle came into sight, we saw an elk doe chilling her knees in the deep mud. She saw us right away and, uninterested in posing for nature art, headed out among the sparse trees with only a couple of backward glances.

Forest graveyard

We had planned to descend to Iron Creek on the other side of the ridge, then retrace our steps back up to the pond and back to camp. But the day was hot, and we had huffed our way up to this high ground, so we preferred to take advantage of the breezes and whatever views we could find.

The catch was that there was only the one trail, and bushwhacking was slow along the hillsides, made uneven by rodent holes and volcanic rubble, and crisscrossed by the corpses of burned trees. At the top of the first rise, we stopped for a snack in a patch of shade. Thankfully, biting insects seemed to be at a minimum here.

The best views from up here, toward the north, were sadly made possible by open stretches where forest had recently stood; and the views themselves showed mainly devastation, across the hills to the horizon. The roughest hiking we would do on this trip was across an obstacle course of fallen trees that were half hidden in the dry sea of high grass, without the relief of any shade.

Finally, we descended into a pleasant incline, a gentle meadow that led us back up to the lake. Returning along our original trail, we clambered over to an outcropping that offered a voyeur’s perspective of our campsite and a good look up the valley.

Renewal

Stiff and grubby, we stopped at the creek to strip, rinse our clothes, immerse ourselves in a shallow hole. It is truly amazing how physical exertion to the point of discomfort, followed by an icy jolt results in a feeling of immortality.

Back at the campsite, we satisfied all remaining bodily requirements and sat down in the shade of the pop-up to contemplate our next moves. Doing the math on gas consumption, we decided that we should have filled up during our second stop at the Glenwood Trading Post, and we hatched a scheme to see if the young Fish and Wildlife guys at the nearby outpost had a couple of gallons to spare.

It took them awhile to hit Pause on their male-bonding session and answer the door. They did report that the road north is vastly better than the one up through Mogollon, but they generously parted with a can-full stored out in the shed with the heavy machinery. They were up here to study the elk, said the presumed leader, but we should keep an eye out for bear, too. He was happy to close the door on this intrusion from the real world, and we didn’t blame him.

Back at the trailer, we sat, our senses calm, watching as a heavy mass of shadow pursued the last of the golden sunlight up the steep hill in front of us. With a backdrop of fiery clouds, a pair of red-tailed hawks emerged above the ridge, wheeling regally until one of them glided away out of sight and the other assumed its throne on the highest branch of the highest tree.

I watched it there, surveying its kingdom, relishing its privileged view of the valley until well after the sun had set, imagining that it had nothing better to do than watch me back. Eventually, after my attention had lapsed for only a moment, I saw that it was gone.

You have to work hard to have fun it seems.

Thanks for transporting me there too with your lovely writing, Michael!

LikeLike

The trick is finding something fun to do for work.

LikeLike

Looks beautiful. Hard to believe it is in America.

LikeLike