There were very few other visitors in the casitas at the lodge; I’m not sure we ever saw any. We always had the common area to ourselves as we enjoyed a savory breakfast of eggs and fruit, and flipped though books from the impressive collection that filled the shelves along one wall.

The night before, in the course of her usual thorough research on our surroundings, Lori had wondered whether we should take the Tour of Houses and Gardens, which is offered only during the mild winter high season, conveniently on Saturdays. She hadn’t even mentioned it to me, though, assuming I’d want to be outdoors instead, and it came up only by accident at breakfast.

Coincidentally, I had picked out a handful of books the night before, and the one I settled on was a brilliant 2008 work from the University of Arizona Press titled Álamos, Sonora: Architecture and Urbanism in the Dry Tropics, by John Messina. The premise of the book is that the layout of the town, going back to its origins as a colonial mining center, is organic to the topography, and that the construction of the houses, most of them now restored by wealthy Americans, is an ideal fit to the bioregion and its climate.

Innocuous exteriors

At 10 a.m., we arrived at the designated corner of the main square, where a small group of Americans had gathered around two expat women, volunteers from Amigos de la Educación de Álamos, which generously provides “full scholarships and other support for secondary school and college” to more than 300 local students.

Our guides took us down a couple of cobblestone side streets, with their raised walkways for the occasional summer floods, toward the northeast corner of the old town. The dwellings formed a continuous façade on both sides of the street from one intersection to the next.

Almost all were clean and painted in a light color – mostly white, peach or tan. Most of the heavy wooden doors and shutters were closed against the bright sun, but now and then a metal gate stood open, offering a view of a lovely courtyard with patterned tile and tropical plants.

Invariably, the guides knew which properties were for sale, and for how much – perhaps a perk of their public service. Suffice it to say that the same amount would buy a dwelling of inferior workmanship and building materials back home.

Unexpected oases

Many of the houses, including the first two of the three we visited, originally had been only segments of larger compounds that over the decades were broken up into several narrow properties. Each of them, though, still has at least one lush interior courtyard that acts as a lung, creating a cooling breeze and expelling heat to the open sky.

In the first house, our hostess was a tiny woman with an outsized smile, an émigré from the Philippines. Her husband, who was off on an errand, showed up at the very end – a retired American professional fully three times her size and maybe twice her age.

The whole place was furnished with antiques; original art populated the walls. All the rooms had high ceilings and a small beehive fireplace in one corner. Every detail spoke of high-quality, earth-based materials and careful hand-craftsmanship.

A narrow wrought-iron staircase led up among the branches of a massive mango tree, sadly out of season, to a view of the nearby rooftops.

Following a dream

The second casa, of a similar size and shape, was presided over by another tall, 70-something expat. A dozen or so years ago, he had bought one larger property, almost entirely in ruins. He had restored the larger portion next door, lived in it while he restored this smaller one, then sold the first one to a friend and moved into the second.

Among his artifacts were a variety of antique firearms and pre-Colombian metates, which he used as doorstops. When I remarked on a wooden chest that stood under a window in the master bedroom, he lit up and pointed out its worn corners, where the woodwork interlocked in seemingly impossible star-like patterns. The knowledge of this craftsmanship is entirely lost to us today, he mused.

On a wooden beam in the courtyard were displayed a couple of ornate saddles that he had made himself. During one colorful interlude in his life – one of several as it turned out – he had renounced the modern world to become a cowboy and apprenticed himself to one of the masters of leathercraft in Montana. Here was a guy who had stuck to his bucket list.

A window in time

His friend who owned the bigger house was out of town, so he showed us around there, too. Speaking for myself, a more pleasant place of repose is scarcely imaginable. It seemed that there was another verdant courtyard around every corner, each with its unique fountain and assortment of plants – bougainvillea, cacti, ferns, fichus, rubber trees, fig trees, banana trees, giant birds of paradise.

Passive dogs lounged on the cool tiles under the overhangs. Now and then, a modest housekeeper could be seen among the shadows, passing from one mysterious space into another.

In one room was a massive table that no doubt had hosted passionate talk of revolution, counterrevolution, enterprise, triumph, despair. In another was an ornate bureau, in another a scarred roll-top desk, in another a wrought-iron chandelier. Folk art and fine art were everywhere.

Around back was a huge walled-in yard, with a veritable grove of fruit trees and a variety of outbuildings – a woodshop, gardening sheds, servants’ quarters, a garage. Above the guest house was a large patio with a nook at one end that offered an unbroken view across the rooftops, the bell tower of the church framed between tall palms.

No doubt the cleanliness, the joyous colors, the classical harmony of the scene in every direction all belied the intensive labor and ongoing expense of maintaining it. Time itself had little meaning here.

A blank slate

Toward the end, we gravitated near our host, ignoring the time’s-up hints of our two tour guides in the hope that they would give up and leave us there to make a deeper acquaintance. Making connections seemed to be his driving impulse as well, and we got a private extension to our tour.

How much of this guy’s epic life was real, how much of it myth can scarcely be established and in fact scarcely matters. With stories of living near Ken Kesey in the canyons of La Honda, of being the family dentist for the Grateful Dead, of spontaneously exchanging one avocation for another and another, he wove the vast tapestry of an alternate reality, at once forgotten and timeless.

In fact, we met him later for dinner – he suggested the Charisma, which we’d had our eye on the night before, a four-star establishment that takes up a whole city block – and a second session of our private lecture. By all measures, he was a kindred spirit – well-read, worldly, enlightened, discouraged by the trajectory of international politics and global health. He had a partner who lived back home in Oregon, but who didn’t share his preference for Mexican culture.

When I mentioned my admiration for the existence he’d created for himself, he did seem open to selling his place. Whether that meant that he could be coaxed back to the States or that he would just turn around and find another casa in need of restoration, I have no way of knowing. He seemed to be someone of unlimited capabilities and possibilities.

Pristine wilderness

Having had perhaps the signature urban experience, we turned our attention to the countryside. As indicated, our lodge sat on the western outskirts, bordering the chief natural attraction, the Parque la Colorada – an international birder’s paradise and prime example of the unique tropical-deciduous biome.

The slanting afternoon sun promised increasing shade within the Parque, which is spread across the facing slopes of the hills west of town. It turned out that we were visiting at the perfect time since the vegetation in this region, in a reversal of the usual expectation, is green during the wet winter and bare during the hot summer.

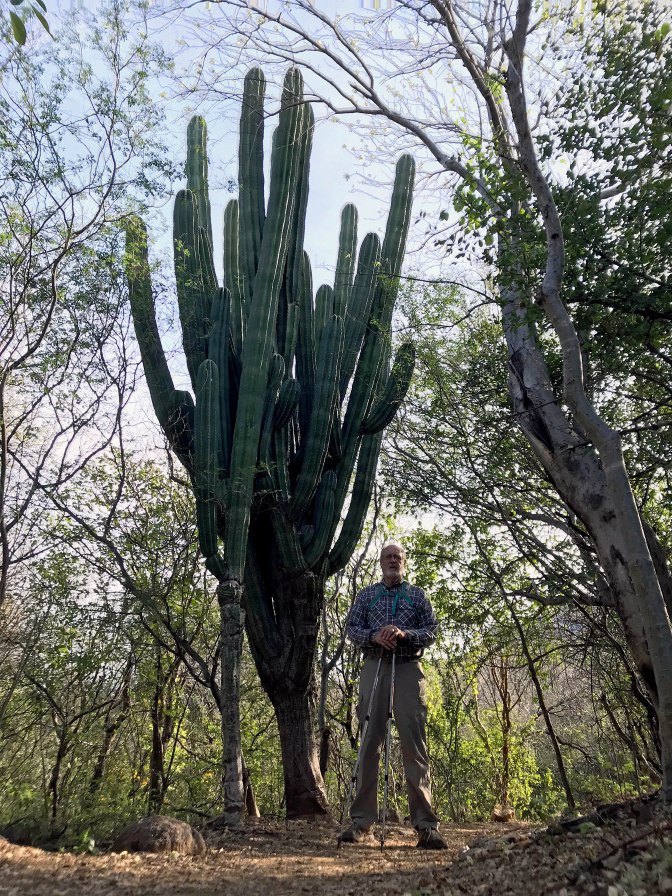

Almost hidden under the forest canopy are massive columnar cacti – colloquially “mountain organ pipes” – which during the arid summer months appear as the dominant plant. At the moment, the forests in every direction were “colored” with the pink smudges of the Amapa tree, effectively the regional mascot, now in full bloom.

The network of trails winds across the low hills and even down into the drainages outside the town. But, for the more ambitious, it also includes steeper options, even switchbacks that climb to progressively higher overlooks with spectacular views of the valley and beyond.

Unexpectedly, the town, with its whitewashed buildings clustered around the church and a few houses farther afield, was a relatively insignificant interruption of the natural landscape. The green carpet stretched unbroken into the distance to the east, finally enfolding the Sierra Madre in the distance.

Deemed unsafe

To the south, we could see the corridor where the highway, 188, descends out of sight before looping back toward the coast. Evidently there is no paved road in the higher country to the east.

Sadly, even the locals tend not to venture out into that wild countryside for fear of bandits. Our expat friend would tell us over dinner that night that a merchant he knew had been robbed some 50 times in the past couple of years, simply writing it off as the price of doing business.

That danger, though, was insignificant compared to the organized crime that dominates the state of Sinaloa, which lies only a few miles away to the south. In our five-day tour of Sonora, we would see no sign of the threats warned of in the State Department travel advisories, but everyone we met admonished us not to push our luck by going any farther south.

The maps indicated that a major reservoir lay beyond the pass to the north, as did the long-running silver mine that had established the town in the first place. Far away in that direction was Copper Canyon – the Grand Canyon of Mexico – long a magnet for tourists, with its train tour along the rim and burro rides into its mile-deep abyss.

We had wondered on the drive down whether we should try to check that off our bucket list on this trip, but it turned out we would have needed another five days. Anyway, that activity – especially the trip over – is no longer deemed safe.