Photos by Lori Stofft, Jodi Latimer, Karma Miller

The first Europeans to arrive at the eventual site of Yuma actually were part of a much larger expedition seeking – ironically, for some cynics – to find the mythical Seven Cities of Gold.

It was nearly 500 years ago when the conquistador Francisco Vásquez de Coronado, having heard of a place where two great rivers converged, sent two detachments to search the region north and west of their base camp at Corazones in what is now Sonora, Mex. The navigator Hernando de Alarcón took the water route up the Sea of Cortez, and Captain Melchior Díaz set off by land – fortunately in autumn – following the future border between Sonora and Arizona.

Díaz, who had the harder job, ended up crossing about 300 miles of bleak desert before he reached the confluence he was looking for. After Díaz wounded himself with his own lance in a freak accident, his men carried him back across the same stretch on a forced march, but he died along the way.

When the task force straggled back into Corazones, they reported that they had traversed the domain of the Devil himself. At the risk of oversimplifying a very long saga, suffice it to say that Coronado headed off in a completely different direction.

El infierno

Its hellish reputation notwithstanding, the region crossed by Díaz’s detail had long been a migratory corridor for indigenous peoples, and it was used by many later European explorers, notably Father Eusebio Kino. Because it had several reliable if well-hidden water sources and because even the Indians avoided this area of sweltering heat and sparse game for much of the year, it was consistently a popular pioneer route, especially for gold seekers in the mid-19thCentury, until the advent of the Southern Pacific Railroad.

Today, the barren tract, one of the most isolated in the entire country, isn’t used for much except bombing practice by air bases located at either end. And of course it is the backdrop for a lively cat-and-mouse game between droves of economic refugees from Latin America and the Wellton sector of the U.S. Border Patrol.

I read recently that the Department of Homeland Security is again waiving environmental and other laws to beef up the barriers along the southern boundary of Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument and the Cabeza Prieta National Wildlife Refuge, the very path of the Devil’s Highway. So I was inspired to recall the trip we took along the historic trail back in the mid-‘90s.

Nearer the heavens

We made this excursion more than 20 years ago, so many of the details are fading from my memory. That was also before we had a digital camera, and the handful of out-of-focus prints we saved aren’t much help in reconstructing the trek of three days and nearly 200 miles of varied terrain.

I do remember that we had to get permits from the Marine base before we left, for the portions of the trip that pass through the Barry Goldwater Air Force Range. We also made a stop at the Wildlife Refuge field office in Ajo, which must have included another round of permits. Those folks probably want to know if someone has gone missing out in that vast wilderness.

By the time we were heading south on the graded road out of Ajo, it was pretty late in the day, so we didn’t make it all that far before we circled the wagons – probably only to Bandeja Well. As with so many primitive campsites around Arizona, the flat ground near the low granite hills was strewn with trash from long-gone mining operations – rotted beams, varicolored shards of glass, 50-gallon drums, heaps of rusted cable and machinery.

With the dying of the campfire, the night was well below freezing. As has happened to me on a couple of winter nights in the desert, I abruptly woke under a vivid blanket of stars gasping for air – presumably an allergic reaction to something in that wild environment. It was a forceful reminder that I wasn’t in the controlled comfort of my cozy home in town.

Fixing fences

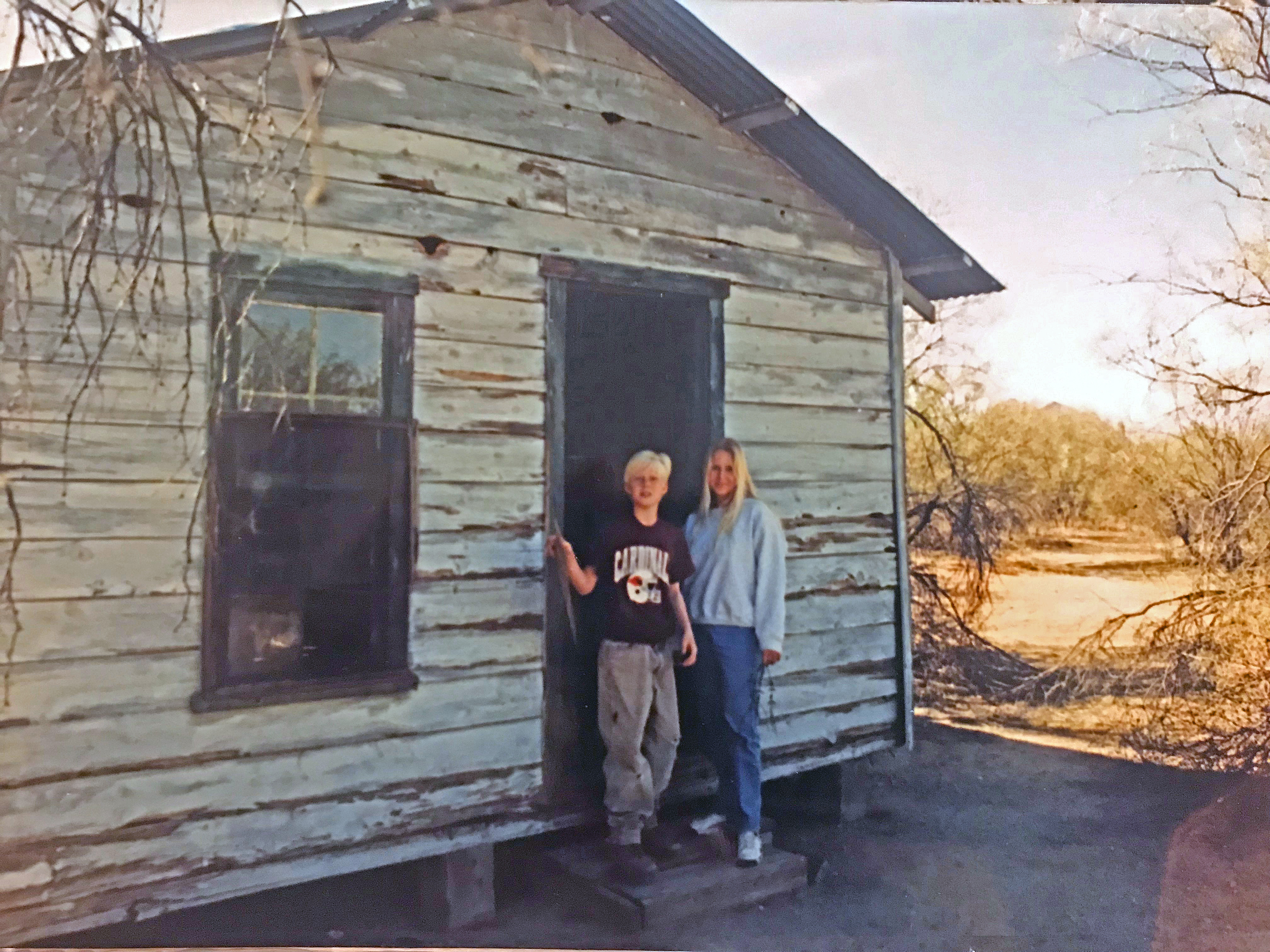

Within a short time on the following morning, we were crossing the northwest corner of the Organ Pipe Monument in our matching pair of blue Jeeps. At Bates Well, we stopped to poke around the wooden cattle pens and dilapidated outbuildings. Before we knew it, my risk-taking preteen was waving to us from the top of the windmill.

Until we had angled another 20 miles or so to the southeast we would not be joining the actual route of the Devil’s Highway, whose origin is at the far corner of Organ Pipe, across the international border in the colonial settlement of Sonoita. Nor would we see the lush oasis at Quitobaquito, which we had passed many times on our way down Mexican Highway 2.

In those days, the only separation between the two countries at that point was a collapsing barbed-wire fence, but no doubt that stretch is vastly more secure today. Sadly, if it is to see the intended barrier upgrade, which won’t be assessed for its environmental impact, this historic water hole will surely be sacrificed since it sits right against the border.

There’s no doubt that unsanctioned immigration at this spot has continued to be an issue. This is the area where, four or five years after our trip, 26 migrants crossed, only to be deserted by their “coyote” guide. In the coming days, 14 of them would die horrible deaths from dehydration and sunstroke before the remainder were rescued by the Border Patrol. The incident brought national attention to the border area and became the subject of a Pulitzer Prize finalist for nonfiction, Luis Alberto Urrea’s The Devil’s Highway.

New ways of seeing

Once the road enters the Cabeza Prieta Wildlife Refuge, it follows close to the border the rest of the way. If we really are going to build a high wall here, it will be visible for much of the route.

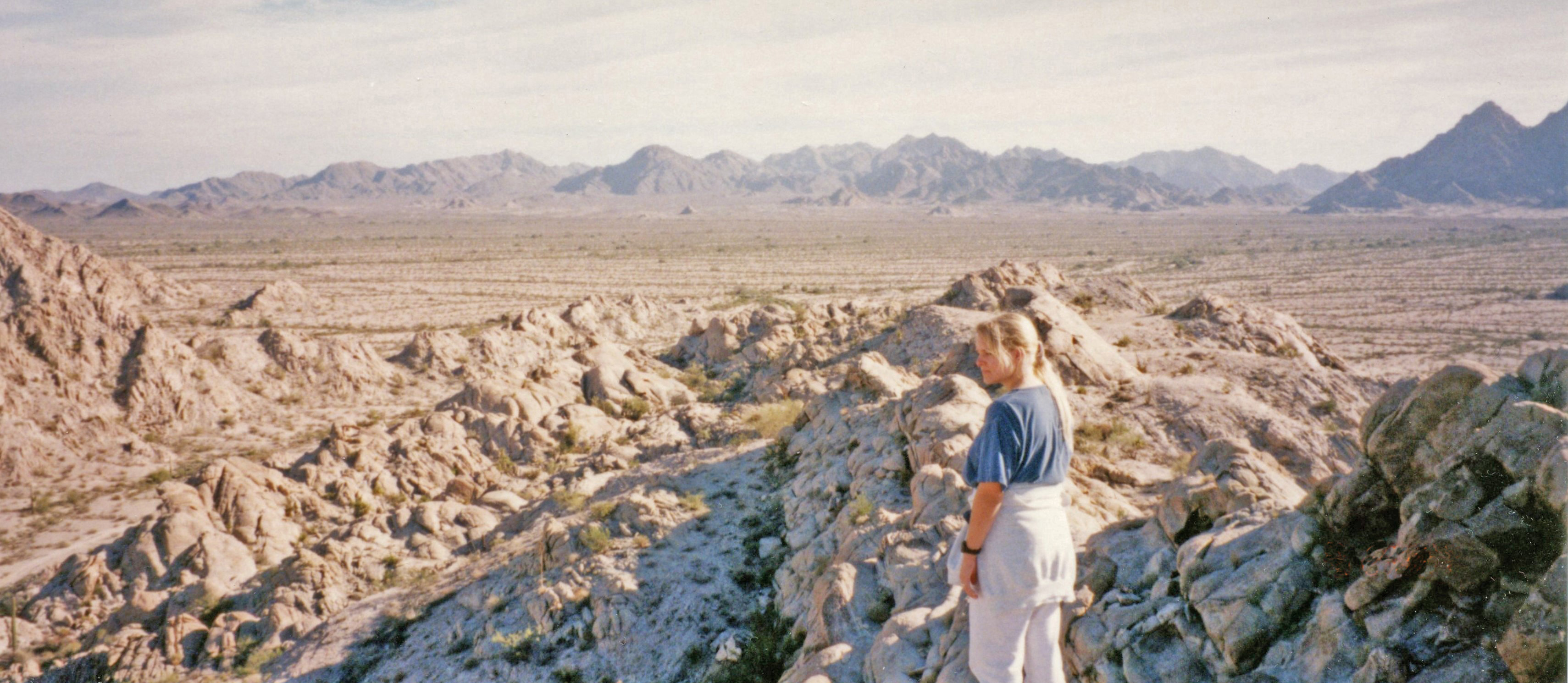

After all these years, what sticks with me about this drive is that it is the only time, except possibly my travels by air, when I have been acutely aware of the Earth’s curvature. One after another, mountain ranges with names like Growler and Sierra Pinta would inch up over horizon and then subside behind us in the rearview.

I was watching eagerly for the massive mound of the Pinacate shield volcano to appear to the south. Sure enough, at the point where we picked our way across a wide stretch of lava flows, the mountain, topped by twin cinder cones, rose up and slowly slid past on our left – a very different perspective than the one I was used to.

At Tule Well, a crossroads between the Cabeza Prieta and Tule Mountains, sat another cluster of wood-slat fences surrounding a quaint cabin, very much intact.

I remember thinking that the late-afternoon light brought the details of the surrounding hills and flats into sharp focus – every boulder, every shade of mineral composition, the spiny outline of every cholla shrub. The still desert air was perfectly clear, and the sky with its broad swaths of high cirrus was an especially deep blue.

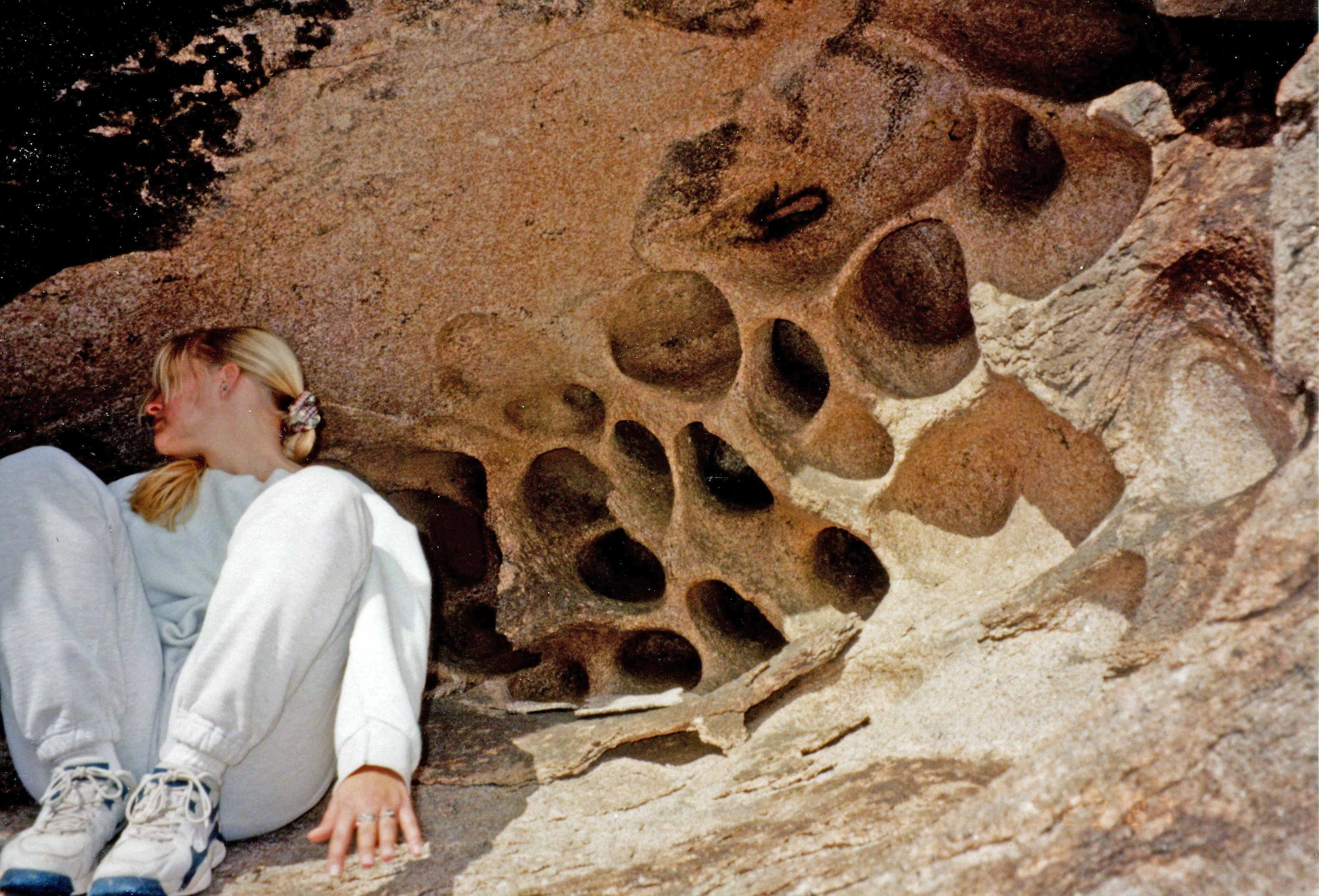

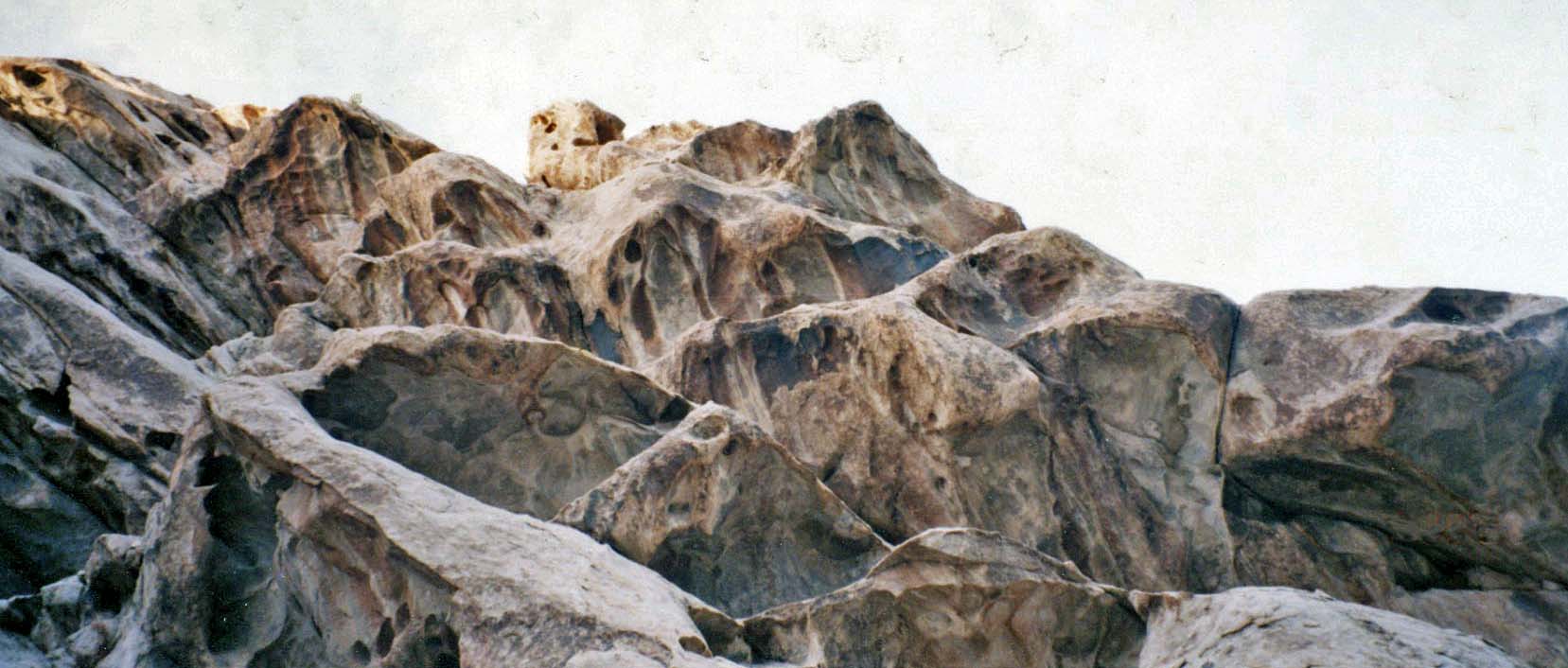

Further along, when we stopped for a rest near Tordillo Mountain, someone in the group found a hillside covered with rare honeycomb quartz, and we took that as a sign that we should set up camp.

Water, water…

It was another cold, damp night, and I spent most of it sitting upright in the front seat of the Jeep, unreasonably fearful that my throat would close again like the night before.

With daylight, in a state midway between waking and dreaming, it took me some moments to realize that the sharp whine I was hearing was the turbo engine of a Border Patrol chopper, which was circling low over our site – seemingly far longer than it should have taken to identify us as affluent citizens playing pioneer. I ordered my two kids out of the tent to display their blond heads.

By the time we reached Tinajas Altas at midday, I was feeling a version – admittedly a modern, pampered version – of the exhaustion and relief shared by all those pilgrims of the previous half-millennium and beyond.

Okay, I hadn’t been in much danger of dying, as so many of them had. We’d seen a few grave markers along the way, though the vast majority had long since been covered up by the shifting sands. The famous story is that not so long ago there had been at least 50 markers at the foot of Tinajas Altas, in recognition of those who had arrived to find the lower catchments empty and who couldn’t muster the energy to climb to the higher ones.

Cat & mouse

After a respectful period of snooping about for native mortar holes and rock art, we set off north on the straight graded road toward Wellton. In the days before I-8, travelers on this eastern side of the mountain spine would have had to go all the way to the Gila River before they could turn west toward the Yuma crossing; so the original Devil’s Highway instead jogged through the pass just north of the tanks. I had explored that route several years earlier, and it was vastly more rugged, winding in and out of washes that drained off the western slopes of the range. Newer gazetteers don’t even show a trail there.

I also have visited Tinajas Altas several other times using the main graded road on the east. Once I was hot-dogging it out of there at 60 mph, no doubt just to see how big a plume of dust I could raise behind me. At about the time I was passing the black cone of Raven Butte on my left, I saw the pale green-and-white paint job of a Border Patrol truck approaching the other way, so I slowed down respectfully.

We drew up opposite, and the agent gave me a nod, satisfied again with my 10-year-old’s blondness. As I pulled away, I saw the helicopter off to the right, kicking up a maelstrom of sand as it hovered just feet above the ground. No doubt he’d been following me for miles, anticipating a dramatic bust.